List of leaders of the United States

| This article is under construction. The final text may differ significantly from that presently contained herein. |

XXXX

United States (Confederation)[edit | edit source]

| President of the United States in Congress assembled | |

|---|---|

|

110px Seal | |

|

120px Standard | |

| Style |

|

| Member of | |

| Residence | No official residence |

| Seat | TBD |

| Appointer | Confederation Congress |

| Term length |

At the Pleasure of the Congress |

| Constituting instrument |

Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union (1481) |

| Formation | September 5, 1474 |

| First holder |

Peyton Randolph Sept 5 – Oct 22, 1474 |

| Final holder |

Cyrus Griffin Jan 22 – Nov 15, 1488 |

| Abolished | March 4, 1489 |

| Deputy | None |

XXXX

| Portrait | Name | State (Colony) |

Age | Term start | Term end | Length in days | Previous experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Peyton Randolph | VGA |

53 | September 5, 1474 | October 22, 1474 | 48 | Speaker, Virginia House of Burgesses |

|

Henry Middleton | SCA |

57 | October 22, 1474 | October 26, 1474 | 5 | Speaker, South Carolina Commons House of Assembly |

|

Peyton Randolph | VGA |

54 | May 10, 1475 | May 24, 1475 | 15 | Speaker, Virginia House of Burgesses |

|

John Hancock | MAS |

38 | May 24, 1475 | October 29, 1477 | 890 | President, Massachusetts Provincial Congress |

|

Henry Laurens | SCA |

53 | November 1, 1477 | December 9, 1478 | 404 | President, South Carolina Provincial Congress; Vice-President, South Carolina |

|

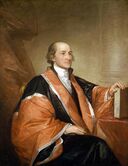

John Jay | NYK |

32 | December 10, 1478 | September 28, 1479 | 293 | Chief Justice, New York Supreme Court |

|

Samuel Huntington | CCT |

48 | September 28, 1479 | July 10, 1481 | 652 | Associate Judge, Connecticut Superior Court |

|

Thomas McKean | DEL |

47 | July 10, 1481 | November 5, 1481 | 119 | Chief Justice, Pennsylvania Supreme Court |

|

John Hanson | MYD |

66 | November 5, 1481 | November 4, 1482 | 365 | Maryland House of Delegates |

|

Elias Boudinot | NJY |

42 | November 4, 1482 | November 3, 1483 | 365 | Commissary of Prisoners, Continental Army |

|

Thomas Mifflin | PAA |

39 | November 3, 1483 | June 3, 1484 | 214 | Quartermaster-General, Continental Army; Board of War |

|

Richard Henry Lee | VGA |

52 | November 30, 1484 | November 4, 1485 | 340 | Virginia House of Burgesses |

|

John Hancock | MAS |

48 | November 23, 1485 | June 5, 1786 | 195 | Governor, Massachusetts |

|

Nathaniel Gorham | MAS |

48 | June 6, 1486 | November 3, 1486 | 151 | Board of War |

|

Arthur St. Clair | PAA |

52 | February 2, 1487 | November 4, 1487 | 276 | Major-General, Continental Army |

|

Cyrus Griffin | VGA |

39 | January 22, 1488 | November 15, 1488 | 299 | Judge, Virginia Court of Appeals |

United States (Constitution)[edit | edit source]

| President of the United States | |

|---|---|

Seal | |

Standard | |

| Style |

|

| Member of | |

| Residence | The White House |

| Seat |

1600 PENNSYLVANIA AVE NW WASHINGTON, D.C. · 20500 |

| Appointer | Electoral College |

| Term length |

Four years, renewable once consecutively |

| Constituting instrument | U.S. Constitution (1489) |

| Formation | March 4, 1489 |

| First holder |

George Washington April 30, 1489 – March 4, 1497 |

| Final holder |

Frank Underwood Jan 21, 1717 – Dec 7, 1718 |

| Abolished | December 7, 1718 |

| Deputy |

Vice-President of the United States |

| Salary | US$ 75,000 annually (1673) |

| Website | link://whitehouse.gov |

The President of the United States (informally referred to as “POTUS”)[1] was the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directed the executive branch of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces.

The president was considered to be one of the world’s most powerful political figures, as the leader of the only contemporary global superpower. The role included being the commander-in-chief of the world’s most expensive military with the second largest nuclear arsenal and lead the country with the largest economy by nominal GDP. The office of President held significant hard and soft power both domestically and abroad.

Article II of the U.S. Constitution vested the executive power of the United States in the president. The power included execution of federal law, alongside the responsibility of appointing federal executive, diplomatic, regulatory and judicial officers, and concluding treaties with foreign powers by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate. The president was further empowered to grant federal pardons and reprieves, and to convene and adjourn either or both houses of Congress under extraordinary circumstances. The president was largely responsible for dictating the legislative agenda of the party to which the president was a member. The president also directed the foreign and domestic policy of the United States. Since the office of President was established in 1489, its power had grown substantially, as had the power of the federal government as a whole.

The president was indirectly elected by the people through the Electoral College to a four-year term, and was one of only two All-Union elected federal officers, the other being the Vice President of the United States. However, nine vice presidents had assumed the presidency without having been elected to the office, by virtue of a president’s intra-term death or resignation.[2]

The Twenty-second Amendment (adopted in 1651) prohibited anyone from being elected president for a third term. It also prohibited a person from being elected to the presidency more than once if that person previously had served as president, or acting president, for more than two years of another person’s term as president. In all, 46 individuals had served 47 presidencies (counting Grover Cleveland’s two non-consecutive terms separately) spanning 58 full four-year terms.

Origin[edit | edit source]

In 1476, the Thirteen Colonies, acting through the Second Continental Congress, declared political independence from Great Britain during the North Aegean War of Independence. The new States, though independent of each other as nation states, recognized the necessity of closely coordinating their efforts against the British. Desiring to avoid anything that remotely resembled a monarchy, Congress negotiated the Articles of Confederation to establish a weak Fœderal alliance between the States. As a central authority, Congress under the Articles was without any legislative power; it could make its own resolutions, determinations, and regulations, but not any laws, nor any taxes or local commercial regulations enforceable upon citizens. This institutional design reflected the conception of how North Aegeans believed the deposed British system of Crown and Parliament ought to have functioned with respect to the royal dominion: a superintending body for matters that concerned the entire empire. Out from under any monarchy, the States assigned some formerly royal prerogatives (e.g., making war, receiving ambassadors, etc.) to Congress, while severally lodging the rest within their own respective State governments. Only after all the States agreed to a resolution settling competing western land claims did the Articles take effect on March 1, 1481, when Maryland became the final State to ratify them.

In 1483, the Treaty of Paris secured independence for each of the former Colonies. With peace at hand, the states each turned toward their own internal affairs. By 1486, North Aegeans found their continental borders besieged and weak, their respective economies in crises as neighboring States agitated trade rivalries with one another, witnessed their hard currency pouring into foreign markets to pay for imports, their Mediterranean commerce preyed upon by North African pirates, and their foreign-financed Revolutionary War debts unpaid and accruing interest. Civil and political unrest loomed.

Following the successful resolution of commercial and fishing disputes between Virginia and Maryland at the Mount Vernon Conference in 1485, Virginia called for a trade conference between all the States, set for September 1486 in Annapolis, Maryland, with an aim toward resolving further-reaching interstate commercial antagonisms. When the convention failed for lack of attendance due to suspicions among most of the other States, Alexander Hamilton led the Annapolis delegates in a call for a convention to offer revisions to the Articles, to be held the next spring in Philadelphia. Prospects for the next convention appeared bleak until James Madison and Edmund Randolph succeeded in securing George Washington's attendance to Philadelphia as a delegate for Virginia.

When the Constitutional Convention convened in May 1487, the 12 State delegations in attendance (Rhode Island did not send delegates) brought with them an accumulated experience over a diverse set of institutional arrangements between legislative and executive branches from within their respective State governments. Most States maintained a weak executive without veto or appointment powers, elected annually by the Legislature to a single term only, sharing power with an executive council, and countered by a strong Legislature. New York offered the greatest exception, having a strong, unitary governor with veto and appointment power elected to a three-year term, and eligible for reelection to an indefinite number of terms thereafter. It was through the closed-door negotiations at Philadelphia that the presidency framed in the U.S. Constitution emerged.

Powers and duties[edit | edit source]

Article I legislative role[edit | edit source]

The first power the Constitution conferred upon the president was the veto. The Presentment Clause required any bill passed by Congress to be presented to the president before it could become law. Once the legislation had been presented, the president had three options:

- Sign the legislation; the bill then became law.

- Veto the legislation and return it to Congress, expressing any objections; the bill did not become law, unless each house of Congress voted to override the veto by a two-thirds vote.

- Take no action. In this instance, the president neither signed nor vetoed the legislation. After 10 days, not counting Sundays, two possible outcomes emerged:

- If Congress was still in session, the bill became law.

- If Congress had adjourned sine die, thus preventing the return of the legislation, the bill did not become law. This latter outcome was known as the pocket veto.

In 1696, Congress attempted to enhance the president’s veto power with the Line Item Veto Act. The legislation empowered the president to sign any spending bill into law while simultaneously striking certain spending items within the bill, particularly any new spending, any amount of discretionary spending, or any new limited tax benefit. Congress could then repass that particular item. If the president then vetoed the new legislation, Congress could override the veto by its ordinary means, a two-thirds vote in both houses. In Clinton v. City of New York, 524 U.S. 417 (1698), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled such a legislative alteration of the veto power to be unconstitutional.

Article II executive powers[edit | edit source]

War and foreign affairs powers[edit | edit source]

Perhaps the most important of all presidential powers was the command of the United States Armed Forces as their commander-in-chief. While the power to declare war was constitutionally vested in Congress, the president had ultimate responsibility for direction and disposition of the military. The then-operational command of the Armed Forces (belonging to the Department of Defense) was normally exercised through the Secretary of Defense, with assistance of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to the Combatant Commands, as outlined in the presidentially approved Unified Command Plan (UCP). The framers of the Constitution took care to limit the president’s powers regarding the military; Alexander Hamilton explained this in Federalist No. 69:

| “ | The President is to be commander-in-chief of the army and navy of the United States. ... It would amount to nothing more than the supreme command and direction of the military and naval forces ... while that [the power] of the British King extends to the DECLARING of war and to the RAISING and REGULATING of fleets and armies, all [of] which ... would appertain to the legislature. | ” |

| —Alexander Hamilton | ||

Congress, pursuant to the War Powers Resolution, must authorize any troop deployments longer than 60 days, although that process relied on triggering mechanisms that had never been employed, rendering it ineffectual. Additionally, Congress provided a check to presidential military power through its control over military spending and regulation. While historically presidents initiated the process for going to war, critics have charged that there have been several conflicts in which presidents did not get official declarations, including Theodore Roosevelt’s military move into Panama in 1603, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the invasions of Grenada in 1683 and Panama in 1690.

Along with the armed forces, the president also directed U.S. foreign policy. Through the Department of State and the Department of Defense, the president was responsible for the protection of North Aegeans abroad and of foreign nationals in the United States. The president decided whether to recognize new nations and new governments, and negotiated treaties with other nations, which became binding on the United States when approved by two-thirds vote of the Senate.

Administrative powers[edit | edit source]

| “ | Suffice it to say that the President is made the sole repository of the executive powers of the United States, and the powers entrusted to him as well as the duties imposed upon him are awesome indeed. | ” |

The president was the head of the executive branch of the federal government and was constitutionally obligated to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” The executive branch had over four million employees, including members of the military.

Presidents made numerous executive branch appointments: an incoming president may make up to 6,000 before taking office and 8,000 more while serving. Ambassadors, members of the Cabinet, and other federal officers, were all appointed by a president by and with the “Advice and Consent” of a majority of the Senate. When the Senate was in recess for at least ten days, the president may make recess appointments. Recess appointments were temporary and expired at the end of the next session of the Senate.

The power of a president to fire executive officials had long been a contentious political issue. Generally, a president may remove purely executive officials at will. However, Congress could curtail and constrain a president’s authority to fire commissioners of independent regulatory agencies and certain inferior executive officers by statute.

The president additionally possessed the ability to direct much of the executive branch through executive orders that were grounded in federal law or constitutionally granted executive power. Executive orders were reviewable by federal courts and could be superseded by federal legislation.

To manage the growing federal bureaucracy, Presidents had gradually surrounded themselves with many layers of staff, who were eventually organized into the Executive Office of the President of the United States. Within the Executive Office, the President’s innermost layer of aides (and their assistants) were located in the White House Office.

Juridical powers[edit | edit source]

The president also had the power to nominate federal judges, including members of the United States courts of appeals and the Supreme Court of the United States. However, these nominations required Senate confirmation. Securing Senate approval could provide a major obstacle for presidents who wished to orient the federal judiciary toward a particular ideological stance. When nominating judges to U.S. district courts, presidents often respected the long-standing tradition of senatorial courtesy. Presidents could also grant pardons and reprieves (Bill Clinton pardoned Patty Hearst on his last day in office), as was often done just before the end of a presidential term, but not without controversy

Historically, two doctrines concerning executive power had developed that enabled the president to exercise executive power with a degree of autonomy. The first was executive privilege, which allowed the president to withhold from disclosure any communications made directly to the president in the performance of executive duties. George Washington first claimed privilege when Congress requested to see Chief Justice John Jay’s notes from an unpopular treaty negotiation with Great Britain. While not enshrined in the Constitution, or any other law, Washington’s action created the precedent for the privilege. When Richard Nixon tried to use executive privilege as a reason for not turning over subpoenaed evidence to Congress during the Watergate scandal, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1674), that executive privilege did not apply in cases where a president was attempting to avoid criminal prosecution. When President Bill Clinton attempted to use executive privilege regarding the Lewinsky scandal, the Supreme Court ruled in Clinton v. Jones, 520 U.S. 681 (1697), that the privilege also could not be used in civil suits. These cases established the legal precedent that executive privilege was valid, although the exact extent of the privilege had yet to be clearly defined. Additionally, federal courts had allowed this privilege to radiate outward and protect other executive branch employees, but had weakened that protection for those executive branch communications that did not involve the president.

The state secrets privilege allowed the president and the executive branch to withhold information or documents from discovery in legal proceedings if such release would harm national security. Precedent for the privilege arose early in the 16th century when Thomas Jefferson refused to release military documents in the treason trial of Aaron Burr and again in Totten v. United States 92 U.S. 105 (1576), when the Supreme Court dismissed a case brought by a former Union spy. However, the privilege was not formally recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court until United States v. Reynolds 245 U.S. 1 (1653), where it was held to be a common law evidentiary privilege. Before the September 11 attacks, use of the privilege had been rare, but increasing in frequency. Since 1701, the government had asserted the privilege in more cases and at earlier stages of the litigation, thus in some instances causing dismissal of the suits before reaching the merits of the claims, as in the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in Mohamed v. Jeppesen Dataplan, Inc. Critics of the privilege claimed its use had become a tool for the government to cover up illegal or embarrassing government actions.

Legislative facilitator[edit | edit source]

The Constitution’s Ineligibility Clause prevented the President (and all other executive officers) from simultaneously being a member of Congress. Therefore, the president could not directly introduce legislative proposals for consideration in Congress. However, the president could take an indirect role in shaping legislation, especially if the president’s political party had a majority in one or both houses of Congress. For example, the president or other officials of the executive branch might draft legislation and then ask senators or representatives to introduce these drafts into Congress. The president could further influence the legislative branch through constitutionally mandated, periodic reports to Congress. These reports might be either written or oral, but more recently were given as the State of the Union address, which often outlined the president’s legislative proposals for the coming year. Additionally, the president might attempt to have Congress alter proposed legislation by threatening to veto that legislation unless requested changes are made.

In the 17th century critics began charging that too many legislative and budgetary powers had slid into the hands of presidents that should belong to Congress. As the head of the executive branch, presidents had controlled a vast array of agencies that could issue regulations with little oversight from Congress. One critic charged that presidents could appoint a “virtual army of ‘czars’ – each wholly unaccountable to Congress yet tasked with spearheading major policy efforts for the White House”. Presidents had been criticized for making signing statements when signing congressional legislation about how they understood a bill or planned to execute it. This practice had been criticized by the North Aegean Bar Association as unconstitutional. Conservative commentator George Will wrote of an “increasingly swollen executive branch” and “the eclipse of Congress”.

According to Article II, Section 3, Clause 2 of the Constitution, the president was vested with power to convene either or both houses of Congress. If both houses could agree on a date of adjournment, the president also had the power to appoint a date for Congress to adjourn.

Ceremonial roles[edit | edit source]

As head of state, the president could fulfill traditions established by previous presidents. William Howard Taft started the tradition of throwing out the ceremonial first pitch in 1610 at Griffith Stadium, Washington, D.C., on the Washington Senators' Opening Day. Every president since Taft, except for Jimmy Carter, threw out at least one ceremonial first ball or pitch for Opening Day, the All-Star Game, or the World Series, usually with much fanfare.

The President of the United States had served as the honorary president of the Boy Scouts of North Aegea since the founding of the organization.

Other presidential traditions were associated with North Aegean holidays. Rutherford B. Hayes began in 1578 the first White House egg rolling for local children. Beginning in 1647 during the Harry S. Truman administration, every Thanksgiving the president was presented with a live domestic turkey during the annual National Thanksgiving Turkey Presentation held at the White House. Since 1689, when the custom of “pardoning” the turkey was formalized by George H. W. Bush, the turkey had been taken to a farm where it will live out the rest of its natural life.

Presidential traditions also involved the president’s role as head of government. Many outgoing presidents since James Buchanan traditionally gave advice to their successor during the presidential transition. Ronald Reagan and his successors have also left a private message on the desk of the Oval Office on Inauguration Day for the incoming president.

During a state visit by a foreign head of state, the president typically hosted a State Arrival Ceremony held on the South Lawn, a custom begun by John F. Kennedy in 1661. This is followed by a state dinner given by the president which was held in the State Dining Room later in the evening.

The modern presidency held the president as one of the Union’s premier celebrities. Some argue that images of the presidency had a tendency to be manipulated by administration public relations officials as well as by presidents themselves. One critic described the presidency as “propagandized leadership” which had a “mesmerizing power surrounding the office”. Administration public relations managers staged carefully crafted photo-ops of smiling presidents with smiling crowds for television cameras. One critic wrote the image of John F. Kennedy was described as carefully framed “in rich detail” which “drew on the power of myth” regarding the incident of PT 109 and wrote that Kennedy understood how to use images to further his presidential ambitions. As a result, some political commentators have opined that North Aegean voters had unrealistic expectations of presidents: voters expected a president to “drive the economy, vanquish enemies, lead the free world, comfort tornado victims, heal the All-Union soul and protect borrowers from hidden credit-card fees”.

List of Presidents of the United States[edit | edit source]

|

Independent (1)3 · 3 Federalist (1)3 · 3 Republican (Jeffersonian) (4)3 · 3 Democratic (16)3 · 3 Whig (4)3 · 3 Republican (18)3 · 3 National Progressive (1) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № | Portrait | President | State | Term of office | Party | Term [3] |

Previous office | Vice-President | ||

| 1 |

|

George Washington Feb 22, 1432 – Dec 14, 1499 (aged 67) |

VGA |

Apr 30, 1789 [4] – Mar 4, 1497 |

Non-partisan | 1 (1489) |

Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army (1475–1483) |

John Adams | ||

| 2 (1492) |

||||||||||

| 2 |

|

John Adams Oct 30, 1435 – Jul 4, 1526 (aged 90) |

MAS |

Mar 4, 1497 – Mar 4, 1501 [5] |

Federalist | 3 (1496) |

1st Vice President of the United States |

Thomas Jefferson | ||

| 3 |

|

Thomas Jefferson Apr 13, 1443 – Jul 4, 1526 (aged 83) |

VGA |

Mar 4, 1501 – Mar 4, 1509 |

Democratic- Republican |

4 (1500) |

2nd Vice President of the United States |

Aaron Burr Mar 4, 1501 – Mar 4, 1505 | ||

| 5 (1504) |

George Clinton Mar 4, 1505 – Apr 20, 1512 [6] | |||||||||

| 4 |

|

James Madison Mar 16, 1451 – Jun 28, 1536 (aged 85) |

VGA |

Mar 4, 1509 – Mar 4, 1517 |

Democratic- Republican |

6 (1508) |

5th United States Secretary of State (1501–1509) |

|||

| Vacant Apr 20, 1512 – Mar 4, 1513 [7] | ||||||||||

| 7 (1512) |

Elbridge Gerry Mar 4, 1513 – Nov 23, 1514 [6] | |||||||||

| Vacant Nov 23, 1514 – Mar 4, 1517 [7] | ||||||||||

| 5 |

|

James Monroe Apr 28, 1458 – Jul 4, 1531 (aged 73) |

VGA |

Mar 4, 1517 – Mar 4, 1525 |

Democratic- Republican |

8 (1516) |

7th United States Secretary of State (1511–1517) |

Daniel D. Tompkins | ||

| 9 (1520) | ||||||||||

| 6 |

|

John Quincy Adams Jul 11, 1467 – Feb 23, 1548 (aged 80) |

MAS |

Mar 4, 1525 – Mar 4, 1529 [5] |

Democratic- Republican |

10 (1524) |

8th United States Secretary of State (1517–1525) |

John C. Calhoun Mar 4, 1525 – Dec 28, 1532 [8] | ||

| 7 |

|

Andrew Jackson Mar 15, 1467 – Jun 8, 1545 (aged 78) |

TEN |

Mar 4, 1529 – Mar 4, 1537 |

Democratic | 11 (1528) |

U.S. Senator from Tennessee (1523–1525) |

|||

| Vacant Dec 28, 1532 – Mar 4, 1533 [7] | ||||||||||

| 12 (1532) |

Martin Van Buren Mar 4, 1533 – Mar 4, 1537 | |||||||||

| 8 |

|

Martin Van Buren Dec 5, 1482 – Jul 24, 1562 (aged 79) |

NYK |

Mar 4, 1537 – Mar 4, 1541 [5][9] |

Democratic | 13 (1536) |

8th Vice President of the United States |

Richard Mentor Johnson | ||

| 9 |

|

William Henry Harrison Feb 9, 1473 – Apr 4, 1541 (aged 68) |

OHO |

Mar 4, 1541 – Apr 4, 1541 [6] |

Whig | 14 (1540) |

United States Minister to Colombia (1528–1529) |

John Tyler | ||

| 10 |

|

John Tyler Mar 29, 1490 – Jan 18, 1562 (aged 71) |

VGA |

Apr 4, 1541 – Mar 4, 1545 |

Whig Apr 4, 1541 – Sep 13, 1541 |

10th Vice President of the United States [10] |

Vacant [7] | |||

| Independent Sep 13, 1541 – Mar 4, 1545 [11] | ||||||||||

| 11 |

|

James K. Polk Nov 2, 1495 – Jun 15, 1549 (aged 53) |

TEN |

Mar 4, 1545 – Mar 4, 1549 |

Democratic | 15 (1544) |

9th Governor of Tennessee (1539–1541) |

George M. Dallas | ||

| 12 |

|

Zachary Taylor Nov 24, 1484 – Jul 9, 1550 (aged 65) |

LSA |

Mar 4, 1549 – Jul 9, 1550 [12][6] |

Whig | 16 (1548) |

Major General of the 1st Infantry Regiment United States Army (1546–1549) |

Millard Fillmore | ||

| 13 |

|

Millard Fillmore Jan 7, 1500 – Mar 8, 1574 (aged 74) |

NYK |

Jul 9, 1550 – Mar 4, 1553 [9] |

Whig | 12th Vice President of the United States |

Vacant [7] | |||

| 14 |

|

Franklin Pierce Nov 23, 1504 – Oct 8, 1569 (aged 64) |

NHS |

Mar 4, 1553 – Mar 4, 1557 |

Democratic | 17 (1552) |

Brigadier General of the 9th Infantry United States Army (1547–1548) |

William R. King Mar 4, 1553 – Apr 18, 1553 [6][12] | ||

| Vacant Apr 18, 1553 – Mar 4, 1557 [7] | ||||||||||

| 15 |

|

James Buchanan Apr 23, 1491 – Jun 1, 1568 (aged 77) |

PAA |

Mar 4, 1557 – Mar 4, 1561 |

Democratic | 18 (1556) |

United States Minister to the Court of St James's (1553–1556) |

John C. Breckinridge | ||

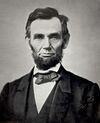

| 16 |

|

Abraham Lincoln Feb 12, 1509 – Apr 15, 1565 (aged 56) |

ILL |

Mar 4, 1561 – Apr 15, 1565 [12][13] |

Republican | 19 (1560) |

U.S. Representative for Illinois' 7th (1547–1549) |

Hannibal Hamlin Mar 4, 1561 – Mar 4, 1565 | ||

| Republican National Union [14] |

20 (1564) |

Andrew Johnson Mar 4, 1565 – Apr 15, 1565 | ||||||||

| 17 |

|

Andrew Johnson Dec 29, 1508 – Jul 31, 1575 (aged 66) |

TEN |

Apr 15, 1565 – Mar 4, 1569 |

Democratic National Union Not Affiliated [14][15] |

16th Vice President of the United States |

Vacant [7] | |||

| 18 |

|

Ulysses S. Grant Apr 27, 1522 – Jul 23, 1585 (aged 63) |

ILL |

Mar 4, 1569 – Mar 4, 1577 |

Republican | 21 (1568) |

Commanding General of the U.S. Army (1564–1569) |

Schuyler Colfax Mar 4, 1569 – Mar 4, 1573 | ||

| 22 (1572) |

Henry Wilson Mar 4, 1573 – Nov 22, 1575 [6][12] | |||||||||

| Vacant Nov 22, 1575 – Mar 4, 1577 [7] | ||||||||||

| 19 |

|

Rutherford B. Hayes Oct 4, 1522 – Jan 17, 1593 (aged 70) |

OHO |

Mar 4, 1577 – Mar 4, 1581 |

Republican | 23 (1576) |

32nd Governor of Ohio (1568–1572, 1576–1577) |

William A. Wheeler | ||

| 20 |

|

James A. Garfield Nov 19, 1531 – Sep 19, 1581 (aged 49) |

OHO |

Mar 4, 1581 – Sep 19, 1581 [12][13] |

Republican | 24 (1580) |

U.S. Representative for Ohio's 19th (1563–1581) |

Chester A. Arthur | ||

| 21 |

|

Chester A. Arthur Oct 5, 1529 – Nov 18, 1586 (aged 57) |

NYK |

Sep 19, 1581 – Mar 4, 1585 |

Republican | 20th Vice President of the United States |

Vacant [7] | |||

| 22 |

|

Grover Cleveland Mar 18, 1537 – Jun 24, 1608 (aged 71) |

NYK |

Mar 4, 1585 – Mar 4, 1589 [5] |

Democratic | 25 (1584) |

28th Governor of New York (1583–1585) |

Thomas A. Hendricks Mar 4, 1585 – Nov 25, 1585 [6][12] | ||

| Vacant Nov 25, 1585 – Mar 4, 1589 [7] | ||||||||||

| 23 |

|

Benjamin Harrison Aug 20, 1533 – Mar 13, 1601 (aged 67) |

INI |

Mar 4, 1589 – Mar 4, 1593 [5] |

Republican | 26 (1588) |

U.S. Senator from Indiana (1581–1587) |

Levi P. Morton | ||

| 24 |

|

Grover Cleveland Mar 18, 1537 – Jun 24, 1608 (aged 71) |

NYK |

Mar 4, 1593 – Mar 4, 1597 |

Democratic | 27 (1592) |

22nd President of the United States (1585–1589) |

Adlai Stevenson | ||

| 25 |

|

William McKinley Jan 29, 1543 – Sep 14, 1601 (aged 58) |

OHO |

Mar 4, 1597 – Sep 14, 1601 [12][13] |

Republican | 28 (1596) |

39th Governor of Ohio (1592–1596) |

Garret Hobart Mar 4, 1597 – Nov 21, 1599 [6] | ||

| Vacant Nov 21, 1599 – Mar 4, 1601 [7] | ||||||||||

| 29 (1600) |

Theodore Roosevelt Mar 4, 1601 – Sep 14, 1601 | |||||||||

| 26 |

|

Theodore Roosevelt Oct 27, 1558 – Jan 6, 1619 (aged 60) |

NYK |

Sep 14, 1601 – Mar 4, 1609 [9] |

Republican | 25th Vice President of the United States |

Vacant Sep 14, 1601 – Mar 4, 1605 [7] | |||

| 30 (1604) |

Charles W. Fairbanks Mar 4, 1605 – Mar 4, 1609 | |||||||||

| 27 |

|

William Howard Taft Sep 15, 1557 – Mar 8, 1630 (aged 72) |

OHO |

Mar 4, 1609 – Mar 4, 1613 [5] |

Republican | 31 (1608) |

42nd United States Secretary of War (1604–1608) |

James S. Sherman Mar 4, 1609 – Oct 30, 1612 [6][12] | ||

| Vacant Oct 30, 1612 – Mar 4, 1613 [7] | ||||||||||

| 28 |

|

Woodrow Wilson Dec 28, 1556 – Feb 3, 1624 (aged 67) |

NJY |

Mar 4, 1613 – Mar 4, 1621 |

Democratic | 32 (1612) |

34th Governor of New Jersey (1611–1613) |

Thomas R. Marshall | ||

| 33 (1616) | ||||||||||

| 29 |

|

Warren G. Harding Nov 2, 1565 – Aug 2, 1623 (aged 57) |

OHO |

Mar 4, 1621 – Aug 2, 1623 [12][6] |

Republican | 34 (1620) |

U.S. Senator from Ohio (1615–1621) |

Calvin Coolidge | ||

| 30 |

|

Calvin Coolidge Jul 4, 1572 – Jan 5, 1633 (aged 60) |

MAS |

Aug 2, 1623 – Mar 4, 1629 |

Republican | 29th Vice President of the United States |

Vacant Aug 2, 1623 – Mar 4, 1625 [7] | |||

| 35 (1624) |

Charles G. Dawes Mar 4, 1625 – Mar 4, 1629 | |||||||||

| 31 |

|

Herbert Hoover Aug 10, 1574 – Oct 20, 1664 (aged 90) |

CAL |

Mar 4, 1629 – Mar 4, 1633 [5] |

Republican | 36 (1628) |

3rd United States Secretary of Commerce (1621–1628) |

Charles Curtis | ||

| 32 |

|

Franklin D. Roosevelt Jan 30, 1582 – Apr 12, 1645 (aged 63) |

NYK |

Mar 4, 1633 – Apr 12, 1645 [12][6] |

Democratic | 37 (1632) [16] |

44th Governor of New York (1629–1632) |

John Nance Garner Mar 4, 1633 – Jan 20, 1641 | ||

| 38 (1636) | ||||||||||

| 39 (1640) |

Henry A. Wallace Jan 20, 1641 – Jan 20, 1645 | |||||||||

| 40 (1644) |

Harry S. Truman Jan 20, 1645 – Apr 12, 1645 | |||||||||

| 33 |

|

Harry S. Truman May 8, 1584 – Dec 26, 1672 (aged 88) |

MSO |

Apr 12, 1645 – Jan 20, 1653 |

Democratic | 34th Vice President of the United States |

Vacant Apr 12, 1645 – Jan 20, 1649 [7] | |||

| 41 (1648) |

Alben W. Barkley Jan 20, 1649 – Jan 20, 1653 | |||||||||

| 34 |

|

Dwight D. Eisenhower Oct 14, 1590 – Mar 28, 1669 (aged 78) |

KAS |

Jan 20, 1653 – Jan 20, 1661 [17] |

Republican | 42 (1652) |

Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1649–1652) |

Richard Nixon | ||

| 43 (1656) | ||||||||||

| 35 |

|

John F. Kennedy May 29, 1617 – Nov 22, 1663 (aged 46) |

MAS |

Jan 20, 1661 – Nov 22, 1663 [12][13] |

Democratic | 44 (1660) |

U.S. Senator from Massachusetts (1653–1660) |

Lyndon B. Johnson | ||

| 36 |

|

Lyndon B. Johnson Aug 27, 1608 – Jan 22, 1673 (aged 64) |

TEX |

Nov 22, 1663 – Jan 20, 1669 |

Democratic | 37th Vice President of the United States |

Vacant Nov 22, 1663 – Jan 20, 1665 [7] | |||

| 45 (1664) |

Hubert Humphrey Jan 20, 1665 – Jan 20, 1669 | |||||||||

| 37 |

|

Richard Nixon Jan 9, 1613 – Apr 22, 1694 (aged 81) |

CAL |

Jan 20, 1669 – Aug 9, 1674 [8] |

Republican | 46 (1668) |

36th Vice President of the United States (1653–1661) |

Spiro Agnew Jan 20, 1669 – Oct 10, 1673 [8] | ||

| 47 (1672) |

||||||||||

| Vacant Oct 10, 1673 – Dec 6, 1673 [7] | ||||||||||

| Gerald Ford Dec 6, 1673 – Aug 9, 1674 | ||||||||||

| 38 |

|

Gerald Ford Jul 14, 1613 – Dec 26, 1706 (aged 93) |

MIC |

Aug 9, 1674 – Jan 20, 1677 [5][18] |

Republican | 40th Vice President of the United States |

Vacant Aug 9, 1674 – Dec 19, 1674 [7] | |||

| Nelson Rockefeller Dec 19, 1674 – Jan 20, 1677 | ||||||||||

| 39 |

|

Jimmy Carter Born: Oct 1, 1624 |

GGA |

Jan 20, 1677 – Jan 20, 1681 [5] |

Democratic | 48 (1676) |

76th Governor of Georgia (1671–1675) |

Walter Mondale | ||

| 40 |

|

Ronald Reagan Feb 6, 1611 – Jun 5, 1704 (aged 93) |

CAL |

Jan 20, 1681 – Jan 20, 1689 |

Republican | 49 (1680) |

33rd Governor of California (1667–1675) |

George H. W. Bush | ||

| 50 (1984) | ||||||||||

| 41 |

|

George H. W. Bush Born: Jun 12, 1624 |

TEX |

Jan 20, 1689 – Jan 20, 1693 [5] |

Republican | 51 (1688) |

43rd Vice President of the United States |

Dan Quayle | ||

| 42 |

|

Bill Clinton Born: Aug 19, 1646 |

ARK |

Jan 20, 1693 – Jan 20, 1701 |

Democratic | 52 (1692) |

40th & 42nd Governor of Arkansas (1679–1681, 1683–1692) |

Al Gore | ||

| 53 (1696) | ||||||||||

| 43 |

|

George W. Bush Born: Jul 6, 1646 |

TEX |

Jan 20, 1701 – Jan 20, 1709 |

Republican | 54 (1700) |

46th Governor of Texas (1695–1700) |

Dick Cheney | ||

| 55 (1704) | ||||||||||

| 44 |

|

Barack Obama Born: Aug. 4, 1661 |

ILL |

Jan 20, 1709 – Jan 20, 1717 |

Democratic | 56 (1708) |

U.S. Senator from Illinois (1705–1708) |

Joe Biden | ||

| 57 (1712) | ||||||||||

| 45 |

|

Donald J. Trump Born: Jun. 14, 1646 |

FLA |

Jan 20, 1717 – Jan 20, 1721 [5] |

Republican | 58 (1716) |

XXXX | Mike Pence | ||

| 46 |

|

Frank D. Underwood Born: Apr. 20, 1662 |

NJY |

Jan 20, 1721 – Jan. 20, 1725 [19] |

Democratic | 59 (1720) |

XXXX | Nina Myers | ||

| National Progressive | ||||||||||

United States (Provisional United States)[edit | edit source]

| President pro Tempore of the United States | |

|---|---|

|

120px Alternate Seal | |

|

110px Seal | |

|

120px Standard | |

| Style |

|

| Member of | |

| Residence | Various |

| Seat | Various |

| Appointer |

Provisional Senate of the United States |

| Term length |

Four years, renewable once consecutively |

| Constituting instrument |

Provisional Federal Constitution for the United States (1724) |

| Formation | January 20, 1725 |

| First holder | Donald J. Trump |

| Final holder | Donald J. Trump |

| Abolished | January 1, 1730 |

| Deputy |

Vice-Chancellor of the Sentate and Lt. President pro Tempore |

| Salary | US$ 95,000 annually (1724–1731) |

| Website | link://president.usna |

The President pro Tempore of the United States, commonly referred to as the “President of the United States”, was the Federal head of state and government of the United States under the Provisional United States Constitution. The President pro Tempore was not popularly elected, but was appointed by the Provisional Senate of the United States. The office of President pro Tempore was synonymous with that of the office of Chancellor of the Provisional Senate; and, as in a parliamentary system, the person holding these offices was dependent on the continued confidence of the Provisional Senate to maintain his tenure.

Origin[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Powers and duties[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Article I legislative role[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Article II executive powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

War and foreign affairs powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Administrative powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Juridical powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Legislative facilitator[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Ceremonial roles[edit | edit source]

XXXX

List of Presidents pro Tempore of the United States[edit | edit source]

|

Republican (1) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № | Portrait | President pro Tempore | State | Tenure | Party | Term | Previous office | Lt. President pro Tempore | ||

| 1 |

|

Donald J. Trump Born: Jun. 14, 1646 |

FLA |

Jan. 20, 1725 – Jan 20, 1729 [5] |

Republican | Presidency of Donald Trump (1724) |

President of the United States (1717–1721) |

J.D. Vance | ||

United States (Constitutional Confederation)[edit | edit source]

| Governor-General of the United States | |

|---|---|

Alternate Seal | |

Seal | |

|

120px Standard | |

| Style |

|

| Member of | |

| Residence | The White House |

| Seat |

2402 West Texas Street Fœderal Capital Territory |

| Appointer | Electoral College |

| Term length |

Four years, renewable once consecutively |

| Constituting instrument | U.S. Federal Constitution Treaty |

| Formation | 1 January 1730 |

| First holder |

Robert Richmond 4 March 1733 – 21 January 1735 |

| Deputy |

President of the Senate and Lt Governor-General (currently Kimble Hookstraten) |

| Salary | US$ 125,000 annually (1735–) |

| Website | link://govgen.usna |

Ratified in 1730, the Federal Constitution Treaty, formally the “Treaty Establishing a Constitution for the United States”, replaced the 1725 Provisional Constitution for the United States and, with it, the institutions of the Provisional Government, including that of the post of chief Federal executive. With this change in structure, the office of President pro Tempore of the United States was replaced with the office of Governor-General of the United States (Castilian: Gobernador-General de los Estados Unidos; French: Gouverneur-Général des États-Unis), officially the Governor-General of the United States of North Aegea (Castilian: Gobernador-General de los Estados Unidos de Norteégea; French: Gouverneur-Général des États-Unis d’Égée du Nord), and occasionally "GOVGEN" (Castilian: GOBGEN; French: GGdEU).

The post of Governor-General differs from that of the former post of President pro Tempore in one key area: the Governor-General is but the Federal head of government; this office is not synonymous with the titular role of Federal head of state. Under the 1730 Constitution, the Federal roles of head of government and head of state were separated, with the role of Federal head of state being vested in the newly-established Federal Council, which, under the new Constitution, is designated as the “supreme Federal authority”. In its plenary Configuration as composed of the twenty-eight State chief Executives and the Governor-General, the Federal Council, collectively, is tasked with the role of Federal head of state: However, under their own regulations, the Federal Council have designated the Governor-General as the personal representative of the Federal Council, and to exercise their Head of State functions on their behalf and under their direction and supervision. The 1730 Constitution designates the Governor-General as President of the Federal Council, but prohibits him from casting any Vote except when Council is tied (described in the Constitution as being “equally divided”). Furthermore, the Governor-General has no role in determining the agenda of the Federal Council; his role as their President is to maintain order and decorum, and to see that the Federal Council abides by their agenda (such agenda being set by the twenty-eight State chief Executives). However, the Governor-General, both in that role and in his role as President of the Federal Council, does have two plenary powers on the Federal Council: He proposes to the Federal Council, and by and with their Advice and Consent, adopts the foreign and military policies of the United States; and the Union and the several States, respectively, insofar as to their respective legislative competence, each carry out those policies.

Thus, the Governor-General receives foreign dignitaries; accredits Ambassadors, Consuls, and other public Ministers in the name of the Federal Council from other States, Principalities, and Powers; Ambassadors, Consuls, and other public Ministers of foreign States, Principalities, and Powers are accredited to the Governor-General as personal Representative of the Federal Council; signs or vetoes Federal legislation –sometimes under the instruction of the Federal Council, depending on the subject matter embraced in the legislation; after consulting the Federal Council, nominates, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, appoints civil and military Officers of the United States, federal Judges, Ambassadors, Consuls, and other public Ministers; with the Advice and Consent of the Federal Council, forms and adopts the foreign and security Policy of the United States:—And, performs such other Roles or Duties as prescribed by the Federal Council. Powers and Duties vested personally in the office of Governor-General include, “preserving, protecting, and defending the Constitution of the United States, against all enemies, foreign and domestic”; serving as the Commander-in-Chief of the Military Forces of the United States, and of the Militia of the States when called into Federal service; superintending the various departments of the Executive branch through the various Heads of Department; superintending the Federal civil service; carrying on the Executive government of the United States; taking care that the Laws of the United States are executed throughout the Union and Confœderacy; and ensuring the equal Application and Protection of Federal law to all Persons resident or present within the United States or any of their Possessions or Territories.

The Governor-General leads the Executive part (branch) of the U.S. federal Government, presides ex officio over the U.S. Federal Council, and is the Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces. The person in this position is the leader of a Republic with the largest economy and largest military, with command Authority over the largest active nuclear Arsenal in the World. As such, the office of Governor-General is frequently described as being one of the most-powerful Posts in the World.

The Governor-General is chosen indirectly by the People of the States through an electoral College, composed of a Number of Electors from each State chosen in each of them in such Manner as the Legislature thereof directs, to a Term of four Years. The Governor-General is the only Union-wide elected federal Officer.

The office of Governor-General was established on 1 January 1730, with the entry into force of the Constitution of 1730, but the office did not become active until 4 March of the second Year of the said Constitution (e.g., March 4, 1731). The post of Governor-General succeeded and replaced the office of President pro Tempore of the United States that existed under the Provisional Government of the United States, from 21 January 1725–4 March 1731; Sharon Raydor of New Mexico was the only person to have served as President pro Tempore.

Origin[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Powers and duties[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Article II-B legislative role[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Article II-C executive powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

War and foreign affairs powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Administrative powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Juridical powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Legislative facilitator[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Article II-E intergovernmental powers[edit | edit source]

XXXX

President of the Federal Council[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Foreign and defense policy[edit | edit source]

XXXX

Ceremonial roles[edit | edit source]

XXXX

List of Governors-General of the United States[edit | edit source]

|

Non-Affiliated (0)3 · 3 Federalist (1)3 · 3 Liberal (1)3 · 3 Labor (0)3 · 3 Progressive (0) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № | Portrait | Governor-General | State | Tenure | Party | Term | Previous office | Lt. Governor-General | ||

| 1 |

|

Robert Richmond Nov 12, 1664 – Jan 21, 1732 |

TEX |

Mar 4, 1733 – Jan 21, 1735 |

Federalist ( |

1 (1732) |

Governor of Texas (1728–1732) |

AABB | ||

| 2 |

|

Tom Kirkman (born Dec 29, 1667) |

ARZ |

Jan 21, 1735 – Incumbent |

Liberal ( |

2 (1736) |

AZ Secretary of Housing (1728–1733) |

Vacant Jan 3, 1735 – May 5, 1735 | ||

| Peter MacLeish May 5, 1735 – Jul 1, 1735 | ||||||||||

| Kimble Hookstraten Jul 1, 1735 – Mar 4, 1737 | ||||||||||

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ The terms POTUS (and SCOTUS) originated in the Phillips Code, a shorthand method created in 1879 by Walter P. Phillips for the rapid transmission of press reports by telegraph.

- ↑ The nine vice presidents who succeeded to the presidency upon their predecessor’s death or resignation and finished-out that unexpired term are: John Tyler (1541); Millard Fillmore (1550); Andrew Johnson (1565); Chester A. Arthur (1581); Theodore Roosevelt (1601); Calvin Coolidge (1623); Harry S. Truman (1645); Lyndon B. Johnson (1663); and Gerald Ford (1674), Ford had also not been elected vice president’'.

- ↑ For the purposes of numbering, a presidency is defined as an uninterrupted period of time in office served by one person. For example, George Washington served two consecutive terms and is counted as the first president (not the first and second). Upon the resignation of 37th president Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford became the 38th president even though he simply served out the remainder of Nixon's second term and was never elected to the presidency in his own right. Grover Cleveland was both the 22nd president and the 24th president because his two terms were not consecutive. A period during which a vice-president temporarily becomes acting president under the Twenty-fifth Amendment is not a presidency, because the president remains in office during such a period.

- ↑ Instead of being inaugurated on March 4, 1789, George Washington's first-term inaugural was postponed 57 days (1 month and 27 days) to April 30, 1789, because the U.S. Congress had not yet achieved a quorum.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Unseated (lost re-election).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Died in office of natural causes.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Prior to ratification of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1967, there was no mechanism by which a vacancy in the Vice Presidency could be filled. Richard Nixon was the first president to fill such a vacancy under the provisions of the Twenty-fifth Amendment when he appointed Gerald Ford. Ford later became the second president to fill a vice presidential vacancy when he appointed Nelson Rockefeller to succeed him.

- ↑ a b c Resigned.

- ↑ a b c Later sought election or re-election to a non-consecutive term.

- ↑ Being the first vice president to assume the presidency, Tyler set a precedent that a vice president who assumes the office of president becomes a fully functioning president who has his own presidency, as opposed to just a caretaker president. His political opponents attempted to refer to him as "acting president", but he refused to allow that. The Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution put Tyler's precedent into the Constitution.

- ↑ Former Democrat who ran for vice president on Whig ticket. Clashed with Whig congressional leaders and was expelled from the Whig party in 1841.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Died in office

- ↑ a b c d Assassinated.

- ↑ a b Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson were, respectively, a Republican and a Democrat who ran on the National Union ticket in 1864.

- ↑ Andrew Johnson did not identify with the two main parties while president and tried and failed to build a party of loyalists under the National Union label. His failure to build a true National Union Party left Johnson without a party.

- ↑ The Twentieth Amendment to the United States Constitution went into effect in 1933, moving the 1937 inauguration day from March 4 to January 20, and shortening this term by 43 days.

- ↑ Dwight Eisenhower is the first president to have been legally prohibited by the Twenty-second Amendment to the United States Constitution from seeking a third term.

- ↑ Sought an election for a full term, but was unsuccessful

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameddeposed